Prague developed over centuries in organic harmony with the landscape around the Vltava River. In accordance with

the biological and spiritual climate and human intervention, a unique urban phenomenon

of a Central European metropolis arose here. The organic growth of the city, often composed

of random and surprising connections between the morphology of the terrain, biological structure, and

architectural forms in various styles, bears witness to its dramatic history and illustrates

the genius loci of this environment, crowned by the expressive and majestic figure of the Hradčany

panorama. There is a remarkable gradation of spaces, characterized by a joyful

and sensitive human scale of buildings and garden scenery, based on the harmony of nature

and tactful human intervention. The influences of Slavic, Jewish, and German cultures,

Mediterranean and Nordic impulses, are reflected here, influencing the atmosphere of local

life in the past and today, with Charles Bridge creating a traditional and symbolic link between them.

Several times during its thousand-year existence, Prague has achieved the highest standards

in terms of political and economic competence and cultural influence from a broad international

perspective, and the character of its architecture is the strongest testimony to this. The first time was in the

14th century, during the High Gothic period under the reign of Roman Emperor Charles IV, who initiated

the construction of the cathedral and Charles Bridge and founded the New Town and the university.

The second time was during the radical Baroque period, when the city was enriched with generous

aristocratic palaces and gardens as well as fascinating temple spaces.

And finally, the third time was during the modern era of the 20th century, when Cubist and

Functionalist architecture was carefully inserted into the historical context of the city center

and more radically on its edges and in the new districts through which the city expanded.

Architecture represented the economic prosperity, self-confidence, and power of the newly born

Czechoslovak Republic. Similar to the era of Charles IV and radical Baroque, Prague became a crossroads

in the interwar period and a place of dialogue for the most important architects of the era, whether it was

Le Corbusier, representatives of the German Bauhaus, or the Dutch avant-garde group De Stijl.

In the early post-war years, Prague was spared major interventions for a long time, and it was not until the

1960s that it expanded with the construction of large prefabricated housing estates, which were subsequently

connected to the city center by metro lines, greatly improving inner-city transport. A number of buildings

were also constructed, signaling the efforts of architects – even under the limited conditions of the socialist

system – to establish a dialogue with developments in world architecture, some of which became important

landmarks. At the same time, care for the historical substance of the city intensified, which eventually

led to Prague’s nomination to the UNESCO World Heritage List in 1992.

The Velvet Revolution in November 1989 brought countless major challenges to the Czech capital –

opening up to the world caused an unprecedented increase in tourism, but above all a massive development

of trade and free cultural activities. Architecture, which in the previous four decades had been

restricted by directive management and the dictates of a construction monopoly, quickly managed to

return to the free professions, and its creators are contributing to the establishment of a

competitive environment, which – from the construction of the “Dancing House” to buildings by

leading foreign architects – is exposed to confrontation with current global trends.

The city’s spatial development department plays an important role in this process, both now and in the

future, in connection with the further development of urban infrastructure and technological changes

at the beginning of the third millennium.

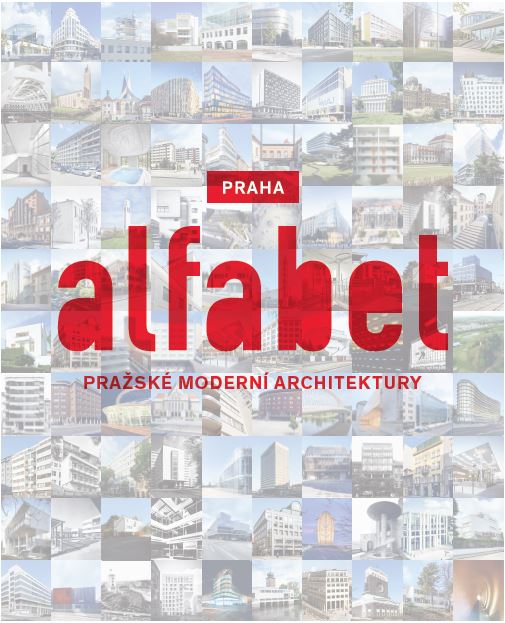

Our publication focuses on the third successful period since 1900, but we extend our

view to the present day. The Prague Alphabet is intended as an aid for walks

for both Czech and foreign architecture lovers, and its short biographies commemorate

the most important creators who have contributed to the modern mosaic of Prague’s buildings.

Vladimír Šlapeta and Patrik Líbal

Čeština

Čeština